article

From Moscow to Vladivostok. It passes through five climate zones, seven time zones, the Ural Mountains and along four of the longest rivers in the world. And spans 9,287 kilometres and 79,000 metres of altitude over 14 stages. These are the incredible numbers that the Red Bull Trans-Siberian Extreme has in store for its participants. Martin Temmen and Matthias Fischer have worked together as a two-man team to finish – and win – the longest stage race in the world. But even these immense figures don’t really illustrate what things are truly like during the race. Like the number games and search for meaning. Martin described what the 13th stage was like for us.

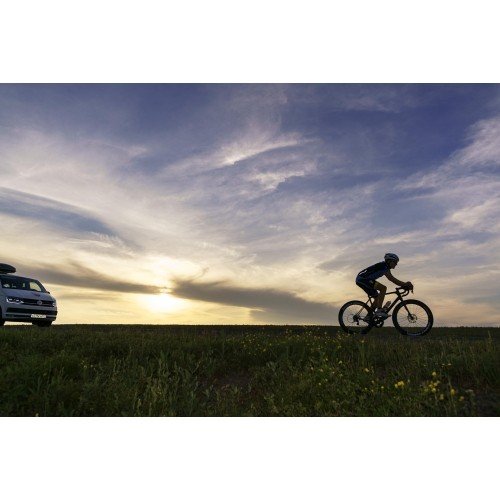

It’s 2.05 in the morning. It’s dark. It’s raining. I look at my on-board computer – I’ve been sitting on my bike for the last 56 minutes. Just a few more minutes to go, then it’s Matthias’ turn. How happy I am! By now, I’m well and truly out of steam. I’m thoroughly exhausted and, for the first time in the last 8,500 kilometres, I can’t see the point in going on. After two minutes, I see a car with its hazard lights switched on next to the road – and the red rear light of Matthias’ PARALANE. A minute later, we high-five. Matthias will ride for the next hour, then it’ll be my turn again. Approximately speaking, there’s another 144 kilometres between us and Chabarovsk. Riding at an average speed of 30 km/h, we’ll be there in just under five hours – three for Matthias, two for me. Then, that’ll be the second-last stage of the Red Bull Trans-Siberian Extreme completed.

I stop, and my escort vehicle stops behind me too. The changeovers are working well by now. Götz, our mechanic, gets out of the car and takes my FOCUS PARALANE to secure it to the carrier mounted on the back of the car. It’s already holding an IZALCO MAX with an Aero attachment for other stages. I’m just standing there and, already, I can feel the first few mosquitoes at my legs, so I get into the car quickly. I sit down on the mattress in the back of the car. This is where I’ve spent most of my time over the last three weeks when not in the saddle.

Alina, our physiotherapist, helps me to take off my shoes and get out of my wet and sweaty clothes. I leave my cycling trousers on. She gives me a dry shirt. I let myself fall onto the mattress. “You’ve left the door open,” Alina remarks. “So what? It doesn’t really matter!” I reply. “No? There are millions of mosquitoes in here now.” So much for that. Götz gets into the car and quickly closes the door behind him. We drive along behind Matthias. The car is actually full of mosquitoes. This doesn’t really lighten the mood with Alina and Götz, who have now been accompanying me for three weeks. It won’t be that bad, I try to tell myself. Think again. What with there being so many mosquitoes in the car, I can’t sleep very well.

I’ve gotten used to the pattern of cycling for an hour and resting for an hour over the last few weeks. During my rest hour, I mainly sleep and eat as much as I can. Today, I suddenly wake up after half an hour and ask Götz and Alina how long I’ve got left. Both of them are just as exhausted as I am and had fallen asleep too. Götz wakes up and looks at the clock. “We’ll have to drive in front in five minutes.” So we can get ahead of Matthias and prepare for the changeover. I let myself fall back again, but I don’t really sleep anymore. After five minutes, we pass Matthias, and park the car after six kilometres. Alina asks me what I want to wear. It’s gotten a bit warmer now, so a jersey, a vest and arm warmers are enough. She gets my things ready and I put them on. I stay sitting in the car for as long as possible, while Götz heads out into the swarm of mosquitoes again to get my bike from the carrier. In addition to fitting mudguards, this should be the only mechanic activity left for him in the race – as we haven’t had any problems at all with our bikes on the road.

The police vehicle, which has been driving along next to us for a few hundred kilometres now, signals to Matthias with its flashlight. I sit on the door baseboard, put on my shoes and overshoes and shuffle up to Götz, who is already waiting on me with my bike which has the lights switched on. I look at the computer, which also indicates the remaining distance to our destination. Matthias has ridden 32 kilometres in the last hour. Now he’s just 50 metres away. I start riding. We high-five, ride another 100 metres alongside one another and have a brief, disjointed discussion: “Only two riding sessions each to go now!” – “I know. All OK with you?” – “I left the car door open: now everything’s full of mosquitoes. Alina and Götz hate me. Never mind. I’m a bit tired, but OK.”

Matthias stops and gets into his car in a similar way to me. I envy him. I’m not just a bit tired. I simply don’t have any strength left and I hate the world. In particular, I hate the race, although we’re riding at the head of the pack, alone. In the overall ranking, we’re a few hours ahead of our competitors. We’ve won ten of the last twelve stages and are on course to win this one too. About halfway through the stage, Matthias pulled away from the rest of the field together with Alexey Shcebelin. After we took turns at leading for a few hours, he had to slow down slightly. And we’ve been pulling ahead since then. The situation actually couldn’t have been any better. But I’m still exasperated. At the moment, I don’t care whether we win this stage or not. I even go as far as thinking that I can’t even be bothered winning. I think, after ten wins, nobody else is interested either – I’d even be happy if the Russian team were to win today.

But most of all, I’d be happy for this stage to finally be over. I’ve been sitting in the saddle for 20 minutes now, riding at a speed of 33 km/h. I calculate again. If we continue riding as quickly as we have been, then there will still be another 70 kilometres to go at the next changeover. And another 38 kilometres to go when it’s my turn again… So another switch wouldn’t be worthwhile. Matthias only has to sit in the saddle one more time, then I’ll just have to cycle a slightly longer section. Should I cycle slower? That won’t help either. In actual fact, I end up going faster. I try not to constantly stare at the computer, so I don’t have a continuous visual reminder of how long we’ve still got to go. I ask myself why this particular stage of “only” 750 kilometres is so difficult for me. The last three days travelling along the key stage of the race, which covers a distance of 1,400 kilometres, was actually a great deal harder. What with a constant headwind and often heavy rain, the individual starters unanimously gave up. Matthias and I managed to complete the stage in 51 hours and had secured a lead of more than three hours on our competitors, Mikhael Manyachin and Roma Markaryan, a Russian duo. We were quite glad we had our PARALANE mudguards during that stage – they kept our trousers dry for a while, at least, and meant we were spared from any sitting problems. While I was able to stoically push through this extremely long stage, Matthias was having a real personal struggle. Today, it’s the other way round – Matthias has enjoyed the ride and chatted away with Alexey, while I’ve started to simply hate everything. Even Matthias. For the simple reason that he’s having fun and I’m not.

Matthias’ car overtakes me after 47 minutes. I now have to sit in the saddle for another 12 minutes and 6 kilometres – a fairly accurate estimation. It doesn’t take me long to work out that my fears are going to be realised – we’ve got another 80 kilometres to go. Taking away the 6 kilometres I’ve still got to cycle, there will be another 74 kilometres remaining when Matthias takes over from me – and roughly 40 kilometres left when it’s my turn again… So it’s really not worthwhile changing again. In spite of that realisation, I’m happy when Matthias relieves me: “You’ve just got to ride once more, then I’ll cycle to the destination.” – “OK, cool!”

When I set off on the last section of the stage, it’s already dawn. The rain has stopped, but the road surface has changed for the worse. Instead of the smooth tarmac we were riding on over the last 100 kilometres, the surface is now alternating between sections with extremely rough tarmac and concrete slabs that are roughly 20 metres long and have huge joins. Every now and again, I also ride past construction sites. Tarmac? Couldn’t be further from the truth! We’ve often been asked for our opinion on the Russian roads over the last few weeks. In our view, the conditions aren’t all that bad. 90% of the roads are good to excellent. The remaining 10% are bad to non-existent. Without any warning, the road often suddenly changes from very good roads to construction sites where the road covering was simply loose gravel, sometimes for several kilometres. Every time, we were very glad about the PARALANE's remarkable suspension. On more than one occasion, our front wheel sunk into a big pothole. We couldn’t imagine the bike, the wheels or even ourselves getting out of there in one piece. But things turned out well every single time, and we didn’t even end up with any flat tyres.

28 kilometres away from our destination, I pass a truck stop. Big dogs are lying in front of it. The situation appears fairly normal and dogs hadn’t really bothered with us so far. This time, though, it’s different. Two giant dogs jump up and run behind me. I speed up, and reach 48 km/h despite my lethargy. The police, who are still escorting us, switch the sirens on. The dogs obey the authorities and leave me alone. I’m awake now, anyway, and somehow the next few kilometres pass slightly quicker at least. The sun has now fully risen and the weather is actually turning out really nice. My mood improves slightly, even though I can’t wait to finally reach the destination. There are just five kilometres remaining when the course leads me across a bridge. I expect the bridge to be a short one, like the hundreds we’ve crossed over the last few days. But this one is crossing the Amur. It is three kilometres long. As the course is constantly heading eastwards, I’m riding into the rising sun. The Amur stretches into an unimaginable vastness on my left and right. I’m completely overwhelmed yet again. I suddenly feel like I’m on cloud nine. I wish this bridge would never end…